Seeing Beyond with Nathan Rice

The moment Nathan Rice snuck a camera out of his parents room, his rebellion set him on a path to becoming the person and award-winning filmmaker he is today.

Photograph by Anthony Ochieng Onyango / National Geographic Society

“I think I was always fascinated by cameras. I used to see people handling cameras. And my dad had a second hand camera that I wasn’t allowed to touch. And at 12 years old, when he was away, I [of course] decided to touch it.

I shot a little movie with my friend and my brother - the three of us made the film and got into trouble for using the camera but when my dad saw what we had filmed he thought it was quite funny so he eased off a bit I was like, ‘Oh, can I touch it again then?’

Even when I got into trouble, even when it was forbidden, my parents somehow let it slide. They weren’t allowed to support me openly, but they never took it away either. I think they understood how much it meant to me.”

All archive photographs courtesy of Nathan Rice

Sharing how he had been thinking up the movie for days, maybe weeks beforehand; planning every shot so that he could be as quick as possible with the camera when he eventually stole it away for their adventure in the forest. Since then, Nathan has not stopped handling cameras and filming, sharing that as soon as he got his hands on an editing suite, he immediately became engrossed in stitching together films. “I've just always been fascinated by it and every new trick you can do. It started off with trying to figure out camera tricks like making a person disappear in the film, magic tricks that you could do or duplicating a person to create a twin. One minute films, two minute films, three minute films. And then it kind of just grew from there, I started creating stories,” he adds.

As a twelve year old boy raised in a remote Christian mission station of just a few hundred people, cameras and fiction were seen as distractions, even transgressions, against the community’s singular devotion to the Bible.

“My brother and I would take the camera into the forest where nobody could see us. We’d come back with footage full of birdsong in the background - at first I thought it ruined the sound, but over time I became aware of those calls, even before I realised how important they’d become in my work.”

Choosing to leave that world, he began studying religion — not to return to it, but to understand it. He attended different churches, researched histories, traced the roots of faith and its contradictions and found he preferred not being religious at all. That curiosity is what underpins his character and storytelling today.

With a penchant for cinema and bringing compelling stories led to graduating from AFDA Durban with a BA in Motion Picture Writing and Directing in 2015.

“There’s a debate within the film industry - a massive debate - to film school or not to film school. It’s the big thing and there are good reasons for and against it. I mean, nobody when you’re making a film is asking for your diploma or your degree or anything like that. It’s all dependent on how good your last film was and that’s what counts in terms of whether you get the next job or not.

For me, obviously coming from a place where I had absolutely no connections within the industry, film school helped me find other people; connect with cinematographers, connect with actors, connect with editors, and just different people. I got to kind of develop a network that still holds to a big extent today. I never would have been able to meet such diverse people from the industry.”

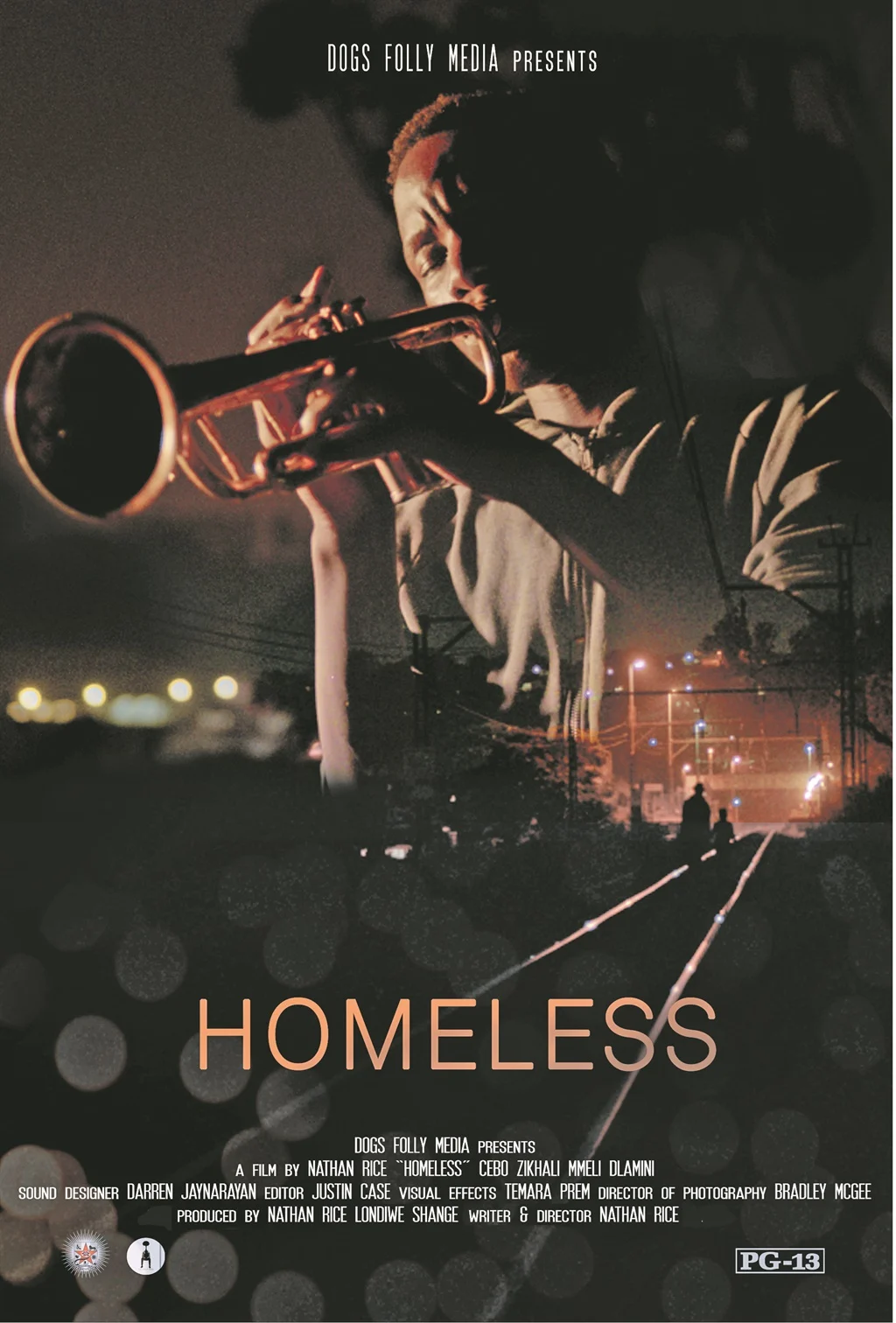

Behind the scenes of Homeless, directed by Nathan.

But film school, for Nathan, wasn’t centred on the classroom. Many of the lectures faded into the background while he poured over books and resources in the library, and experimented with film in and out of the studio. These were ways he committed to expanding his world and process. What mattered most was the freedom to experiment — to make mistakes, test genres, and push himself into new ways of telling stories.

Seven short films later, he walked away with a portfolio that no self-funded hustle at that age could have produced, and more importantly, a network of collaborators who remain part of his journey.

Behind the scenes of Homeless.

“...if you’re a film director, you get to direct films, you get to practice making films. Each term you come back you make another film, put it up and that constant feedback within a safe space of school - space and time to actually practice making a film and showing it to people.

That was extremely helpful - I came out of school with seven short films that I never would have gotten the opportunity to do if I had to try and raise a budget, put a crew together and all of that. The practical applications were really like almost a long lab to just experiment with different formats and approaches to your craft, I could research and experiment with filming different genres.It was very cool to try different things out and see what I liked and what I didn’t like. You’re just immersed in the actual stories; so for me it was a very positive experience.”

In 2016, Nathan co-founded Untitled Entertainment with John Hlongwane, his debut feature, The Road Less Cycled (2020), mentored by Sarah Blecher, premiered on Amazon Prime Video. He co-directed Lilith: The Ground Beneath Her Feet (2022) with his brother. He has worked on fiction and non-fiction projects, winning awards for short films like Dream Writer (2022), Ngikhona (2021), and Faulty (2017). His documentary projects as a DOP and editor include short film Hluleka (2020), and a biography film profiling Dadzie Carlos under the African Science Film Fellowship by NEWF and African Wildlife Foundation.

“I saw film as drama, as fiction. Nature was in the back of my mind from those early years running around the forest but it was never something I joined together with my idea of film. I wasn’t thinking about connecting nature and storytelling until Noel Kok - Co-Founder and Executive Director of NEWF - invited me to work with Mlugisi Ntuli to film and edit The River Gives.

That project opened my eyes. Documentary films are not just about information. It’s about storytelling, it’s human - and it can change the way people see the world.”

Still frame from The River Gives.

And in deepening his attention to the natural world through documentary - particularly birds - what began as background noise in his earliest films took centre stage in Grassland (2022), a film conceptualised by and featuring his partner Katie Biggar. Filmed and edited by him the ways sound, rhythm, nature and community were at the centre.

Behind the scenes of Grassland with Katie Biggar.

“When you’re editing, you start noticing patterns. Birds calling at certain times of day, certain seasons. You realise they’re not just in the background — they’re part of our story.”

Willingness to fail, to try genres outside his comfort zone, to learn through doing, prepared him for what would come as he experienced growth and opportunity in the NEWF community where he met Katie, a biological scientist, as well as many other collaborators like Tembisa Jordaan and the master scientists from the African Science Film Fellowship.

In the NEWF network he found collaboration extended far beyond film. “I was meeting scientists, conservationists, storytellers who weren’t behind a camera at all. I realised that this is the point. Film is a representation of something greater,” he shares.

Expanding on this, he joined the crew of Ulwandle Lushile(2020) - a project by Tembisa Jordaan, a marine scientist, cook and fellow - as a DOP and editor, a new opportunity to refine and expand his process as a filmmaker. The film featured in a roster of festivals and placed second in the 2021 Yale Environment 360 Video Contest. The film remains relevant today, offering a case study for community-inclusive conservation and ethical storytelling.

“She had this amazing community and story, but we weren’t sure of what the film would look like. Through our conversations, I could see where the pieces were missing, we needed to listen to what it was and close the circle — show the women leaving home, collecting mussels, and then returning to put food on the table. It was a journey. You had to walk with them, and bring the broader community and audience into the rhythm of their lives.

When people talk about food and culture, they don’t always see it as conservation. But watching these women, you realise: this is conservation. This is knowledge passed down, rooted in respect for nature, for timing, for community. That’s the story.”

Title frame from Ulwandle Lushile.

With NEWF, he has participated in cinematography training both as a fellow, and working with emergent talent in the field to share his lens and enhance their skillset and confidence. As part of the 2025 Field Navigation Lab with Massimo Rebuzzi, it provided an incredible opportunity to immerse in KZN’s terrestrial landscapes and return to his fascination with birds.

“I admit not everyone gets to do multiple labs or jump straight into opportunities but the special thing about NEWF is that the opportunities are there. You grow, you develop, you get to learn from other fellows, and when the time is right, you step into projects that feel like the next step in your career.”

Still frame from BTS of the 2025 Field Navigation Lab.

Nathan’s filmmaking brings together strands that at first seemed irreconcilable: his early rebellion against a closed world, his fascination with story, his curiosity about religion, and his growing recognition of nature as a guide, collaborator, and character. It’s here his journey truly reflects the spirit of NEWF itself: a space where talent is not only nurtured but also revealed through time, practice, and the collective energy of a community that believes in telling Africa’s stories, in Africa’s voice.

“Coming out of a closed-off community, I had always been told that without religion, people had no morals. Then suddenly I met people with the most fascinating moral compasses, people who weren’t religious at all. It expanded my mind. I realised morality doesn’t have to come from a book — it can come from reasoning, from observation, from the way you want to live within a community.”

That ability to hold complexity — difference and belonging, disagreement and love — is mirrored in his filmmaking, shaping his perspectives, culture and the rhythm of diverse people's lives. Joining projects like Indoni Yamanzi and Wild Hope Rhino Ops came at a time where his experience, breadth of perspective, work ethic and insatiable curiosity took root anew.

With Indoni Yamanzi the story belonged not only to the ocean, but also to local matriarch, Silindile Mbuyazi. From a diver with limited sense of place in the ocean world, to becoming a leader whose voice now carries far and wide. She’s not a background character anymore. She’s the centre, and that intimacy richly contributes to the film. Unlike research-driven projects, this one grows out of lived conversations, dinner-table storytelling, and years of community.

Still frame from the Indoni Yamanzi teaser.

“It’s not something you have to look up in a paper. Every time you sit with her, a new detail emerges. You live the story with her. She’s not bombarding people with facts. She wants to bring the stories home, make the ocean relatable, create opportunities for people who never thought they belonged there.”

What fascinates Nathan is the way Sli has reclaimed the ocean as something she is intrinsically part of. Once fearful of it, she has reinterpreted it through her grandmother’s folktales, through scientific knowledge, and through her own community’s lens — making it both something that belongs to her, and is shared with others.

If Ulwandle Lushile taught Nathan anything about story structure and patience, and Indoni Yamanzi about intimacy and belonging, then filming the Rhino Dehorning Project — was something else entirely: a pressure test on his Directing skillset. He and a diverse, talented team worked under the guidance of Geoff Luck, a veteran conservation filmmaker whose methods are, in Nathan’s words, a lot like a storytelling bootcamp. Reflecting on Geoff's mentorship throughout he notes how much growth he experienced through Geoff’s trust — he was there but really allowed Nathan and the crew at large to lead production.

“I really had to take ownership. I was accountable. Cameras rolled from sunrise to sunset, we were managing gear, checking audio, thinking through shots in real time with no second chances — if you missed it, you missed it. But I never felt unsupported.”

The film itself carries a heavy subject, one close to the NEWF community origin story — rhino poaching and conservation in South Africa, but what he remembers most vividly is the intensity of the process because that sense of accountability defined the shoot.

“As the filmmaker you need to know that your story is sound, that there’s a flow. If we make a change, what is the impact on what you are saying? The story arc itself needs to make sense. So that was super affirming for me.”The script is relevant all the way through, from the very early development. You’re constantly going back to it throughout the shoot. Once you finish the first cut, you update the script again. Only once you lock the edit, then it’s like, okay, now we’re done with the script.”

Working through script and story hand in hand — left a lasting mark. It reframed how he thought about filmmaking, giving him a structure to return to for future projects.

Post-production, however ,changed his perspective the most. Editing was not simply a technical exercise, but an extended dialogue with the story. While the final grading and sound mixing took place in Washington D.C., Nathan shouldered much of the editing work locally.

“The fascinating thing was how throughout the editing process, they retained the film as a script — constantly in word format. So when you make an edit of the film you don’t just submit the cut, they don’t even care about the cut. Once you’ve cut it, you rewrite the script. So the whole edit is put into a script format and they work from there.”

Wild Hope Rhino Ops in post-production at the Wild Hope studios in Washington D.C.

For him, this method was transformative. Instead of being distracted by shots or sequences, the discipline of rewriting forced clarity: was the story intact? It confirmed instincts he had long been turning over in his mind.

That final stage — grading and mixing at state-of-the-art facilities — gave him a chance to release some of the tension. After months of being consumed by story and structure, it was a relief to focus on sound, colour and atmosphere.

“Working at the end of that process with professional sound mixers and designers, colour graders — when you’ve been working just on story, story, story all along – you get to step back and just focus on the visuals and the sound. You get to enjoy the film and can’t fix anything anymore, so you look at it for what it is now. I just wanted some popcorn, to sit back and watch the film.”

Nathan Rice (Write, Director, Editor), Ntokozo Mbuli (Assistant Producer), Carlos Noronha (Director of Photography) and Anthony Njuguna (Second Camera and Drone Operator).

“Everyone was focused, everyone had a role, and it demanded everything we had. It showed me what I was capable of, but it also showed me how much stamina this work requires.”

That stamina is tested in new ways now that Nathan is a father. Parenthood, he admits, has reframed almost everything. Being away from home often, he admits that it’s tough loving the work you do, and being home with your family. A new source of commitment to trial, error and adaption in the pursuit of more balance that constantly ask how much to give to your work, and how much to give to your family. He speaks with tenderness about his partner and daughter, describing how even the smallest moments feel like revelations.

Nathan with his toddler daughter, Elise.

Future fellow Elise doing a gear check with her dad.

“It’s beautiful to see a human growing and becoming something almost from nothing. You realise how everything in their environment is influencing them. I didn’t have a wide diversity of experiences growing up, but now I do. And I want to introduce her to all of it — the people, the ideas, the possibilities. Just to let her know how much the world can be. I can’t wait until she’s old enough to come with me on trips — to experience the world first-hand, to see the possibilities for herself.”

Already, he takes her out each morning he is home, pointing out the birds and trees, hoping to spark that same sense of noticing that once shaped his own filmmaking. What he carries forward is not just a body of work, but a legacy — of curiosity, custodianship, resilience, and of creating spaces where both stories and people can be seen.